January Response

Last month, we looked at the case of a young patient under the care of her mother, who declined the HPV vaccination on behalf of her daughter. Here’s another look at the situation:

A 12-year-old female presents to your clinic for their regular well-child examination. You recommend the following immunizations: Tdap, first HPV vaccine, and the first meningococcal vaccine. The mother consents to all vaccinations except for the HPV vaccine. She states that her child is not sexually active. You then proceed to inform both the mother and patient that per the CDC, it is recommended that 11- to 12-year-olds get two doses of HPV vaccine to protect against cancers caused by HPV. Ideally, females should get the vaccine before they become sexually active and are exposed to HPV. The mother continues to decline the HPV vaccine and says that she has the final say in her child’s well-being.

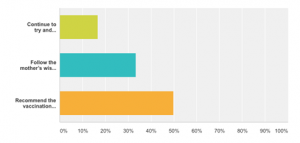

Which of the following actions would you proceed with?

- Continue to try and convince the mother to consent to the HPV vaccine by informing her that health insurance plans cover the cost of HPV vaccine and the Vaccines for Children (VFC) program may be able to help if they are not insured. Beneficence of the population outweighs self-autonomy of one.

- Follow the mother’s wishes and no longer continue to discuss the matter. Self-autonomy is of greater importance when it comes to patient health care.

- Recommend the vaccination once more but also recommend additional HPV and cervical cancer prevention methods such as condoms, limiting the number of sexual partners, and regular cervical cancer screening.

The figure above shows the results of our poll. More of our participants chose answer C than any other answer, choosing beneficence to the patient above self-autonomy. About half of our participants were split between answers A and B, choosing beneficence of the population and self-autonomy, respectively.

March Question

On a breezy March night, you are rounding on your final group of patients for the evening. It is already an hour after your shift ended, but you stayed to attend to the needs of a particularly emotional family that has been badgering you with questions regarding their loved one all day. Suddenly, you hear “Code Blue” over the hospital intercom. It is a patient assigned to your team. She is an elderly woman who arrived earlier this week from a nursing home. She suffers from congestive heart failure and type 2 diabetes and is morbidly obese. A recent bout with pneumonia has rendered her dependent on a ventilator, and her condition has continued to deteriorate. She does not have an advanced directive. Your attending physician had previously mentioned that she would never be able to breathe on her own again and that he considered further care futile.

What is the best step to protect your patient?

- The patient will not benefit from further treatment or from resuscitation. It would be cruel to subject her to the harsh physical treatment of a full code. Do not perform ACLS or any other intervention.

- Perform a “walking code” in which you do not rush to the scene and continue full code protocol more slowly than usual. This protects the hospital and team from liability but also protects the patient’s dignity by preventing a full code.

- The patient should be saved at all costs. You do not know her wishes in regards to end-of-life treatment, so you must do everything that you can to prolong her life.

Tell us what you think!

Bridget Ralston is a member of The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix Class of 2020. She graduated from Santa Clara University in 2015 with a Bachelor of Science in Chemistry and a French minor. She de-stresses by whipping up delicious treats (and subsequently devouring them), playing soccer, and cuddling with her cat, Tuxedo. She has a particular interest in healthcare for underserved communities.