March Question

In March, we looked at the case of a terminal patient without an advanced directive. Here’s a reminder:

On a breezy March night, you are rounding on your final group of patients for the evening. It is already an hour after your shift ended, but you stayed to attend to the needs of a particularly emotional family that has been badgering you with questions regarding their loved one all day. Suddenly, you hear “Code Blue” over the hospital intercom. It is a patient assigned to your team. She is an elderly woman who arrived earlier this week from a nursing home. She suffers from congestive heart failure and type 2 diabetes and is morbidly obese. A recent bout with pneumonia has rendered her dependent on a ventilator, and her condition has continued to deteriorate. She does not have an advanced directive. Your attending physician had previously mentioned that she would never be able to breathe on her own again and that he considered further care futile.

What is the best step to protect your patient?

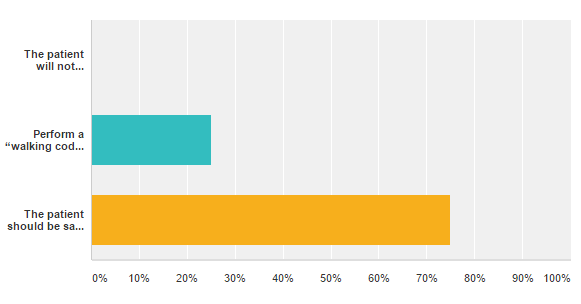

- The patient will not benefit from further treatment or from resuscitation. It would be cruel to subject her to the harsh physical treatment of a full code. Do not perform ACLS or any other intervention.

- Perform a “walking code” in which you do not rush to the scene and continue full code protocol more slowly than usual. This protects the hospital and team from liability but also protects the patient’s dignity by preventing a full code.

- The patient should be saved at all costs. You do not know her wishes in regards to end-of-life treatment, so you must do everything that you can to prolong her life.

Here are the results of the survey:

Most responders agreed that the patient should be saved at all costs, putting the ethical principle of beneficence to the patient above other considerations. Other responders considered the “walking code,” a good option to help save the patient from further harm, which holds the patient’s dignity and non-maleficence to be more important. The question is a difficult one to answer for many physicians and healthcare workers, but it is one they are faced with frequently.

May Question

You sit down in front of your own physician, speechless. Although you’ve given many patients the same news in an equally gentle manner, it somehow doesn’t feel the same when you’re hearing it about yourself. You’re dying. It won’t be any time soon, but you’ve been diagnosed with a terminal cancer. You remember learning in medical school that most patients with this cancer live 3-5 years, with debilitating symptoms for the last year and a half. You begin to wonder who will take on your patients and how you will leave your practice and when. Many of your patients are undocumented, and their healthcare options are limited. You ask your physician for advice.

What is the best course of action?

Tell us what you think!

Bridget Ralston is a member of The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix Class of 2020. She graduated from Santa Clara University in 2015 with a Bachelor of Science in Chemistry and a French minor. She de-stresses by whipping up delicious treats (and subsequently devouring them), playing soccer, and cuddling with her cat, Tuxedo. She has a particular interest in healthcare for underserved communities.