May Ethical Question

In May, we discussed the possibility of acquiring a terminal disease and the end of a physician’s life. Let’s revisit:

You sit down in front of your own physician, speechless. Although you’ve given many patients the same news in an equally gentle manner, it somehow doesn’t feel the same when you’re hearing it about yourself. You’re dying. It won’t be anytime soon, but you’ve been diagnosed with a terminal cancer. You remember learning in medical school that most patients with this cancer live 3-5 years, with debilitating symptoms for the last year and a half. You begin to wonder who will take on your patients and how you will leave your practice and when. Many of your patients are undocumented, and their healthcare options are limited. You ask your physician for advice.

What is the best course of action?

- Notify your patients of your illness immediately, but stay in practice until your symptoms become unmanageable. Your patients are your first priority.

- Don’t notify your patients and practice up until you make a mistake or are physically incapacitated. It is your duty to care for your patients until you are unable, but it would be inappropriate to reveal personal details to them.

- Notify your patients immediately and close your practice as soon as possible. You want to spend the last years of your life with your family and friends, traveling or practicing your favorite hobbies.

- Practice for another year until all of your patients have been referred to other practices, then retire. It is important to care for your patients, but also for yourself.

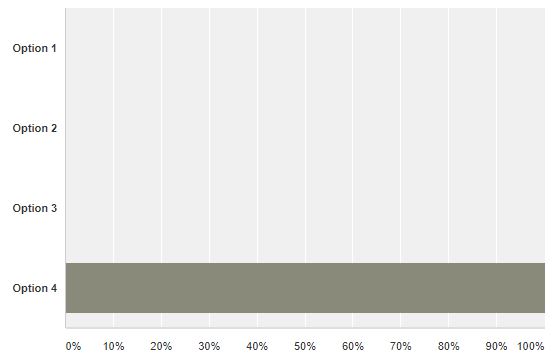

The results were unanimous. All survey responders chose Option 4, to take time for themselves and family while ensuring the safety and care of their patients.

The results were unanimous. All survey responders chose Option 4, to take time for themselves and family while ensuring the safety and care of their patients.

July Ethical Question:

You are a general practitioner and a mother comes into your office with her child who is complaining of flu-like symptoms. Upon entering the room, you ask the boy to remove his shirt and you notice a pattern of very distinct bruises on the boy’s torso. You ask the mother where the bruises came from, and she tells you that they are from a procedure she performed on him known as “cao gio,” which is also known as “coining.” The procedure involves rubbing warm oils or gels on a person’s skin with a coin or other flat metal object. The mother explains that cao gio is used to raise out bad blood, and improve circulation and healing. When you touch the boy’s back with your stethoscope, he winces in pain from the bruises. You debate whether or not you should call Child Protective Services and report the mother. (Taken from the Santa Clara University Markkula Center for Applied Ethics Medical Ethics Case Studies)

Tell us what you think!

- Santa Clara University Markkula Center for Applied Ethics

Bridget Ralston is a member of The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix Class of 2020. She graduated from Santa Clara University in 2015 with a Bachelor of Science in Chemistry and a French minor. She de-stresses by whipping up delicious treats (and subsequently devouring them), playing soccer, and cuddling with her cat, Tuxedo. She has a particular interest in healthcare for underserved communities.