Likely, all of us in middle school or high school had to take an art class—a drama class, band, or art class maybe. Believe it or not, I thought I was awful at all of those; my doodling always was the same set of circles, and I am sure somebody would have paid me to not take a choir class. So instead, I took art history for the one year my school offered it and loved it.

What does this have to do with medicine? Everything. Ask any anatomy student or surgery resident who is currently staring at a Netter’s textbook.

Diagram of the Nervous system, late 13th century

Medical illustration was a method of disseminating knowledge in the early days. Hellenic Alexandria in the early 3rd century BC was a hub for medical research where many began drawing on various topics, including anatomy, surgery, and obstetrics, and documenting plants that had medicinal properties[1]. Galen and Hippocrates were among the most noted medical historians of the time, dominating medical thought for the next 1500 years in the theories of the four humors. During the Middle Ages while Europe was falling into the Dark Ages, much of medical knowledge and study was preserved in the Muslim world. Scholars of Islam at the time found studying anatomy as a way to demonstrate the design and wisdom of Allah [2]. During the late 13th century, the Syrian physician Ibn al-Nafis even described and outlined the movement of blood through the pulmonary system, approximately 300 years prior to the first European description of the pulmonary system [2].

Artists themselves dissected bodies to understand the intricacies of musculature and organ systems for their art. Michelangelo made countless anatomical sketches, the basis of which informed his depictions of The Last Judgment, and studies during his training by analyzing the corpses of a Florentine church’s hospital [3]. Leonardo da Vinci is responsible for the first accurate depiction of the human spine; his notes during one dissection are currently known as the earliest description on record of cirrhosis of the liver. He also asserted that the heart was a four-chambered organ with synchronous cycles of rotational contraction and relaxation at a time when many considered the heart a simple two-chambered organ. Many of these findings were never published [4].

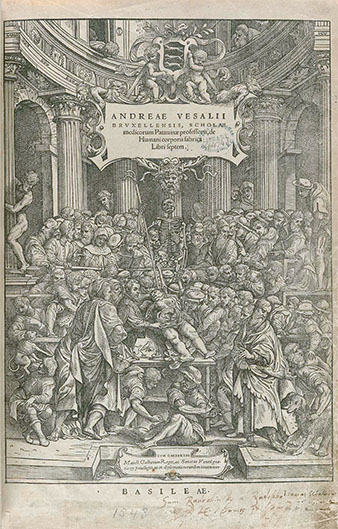

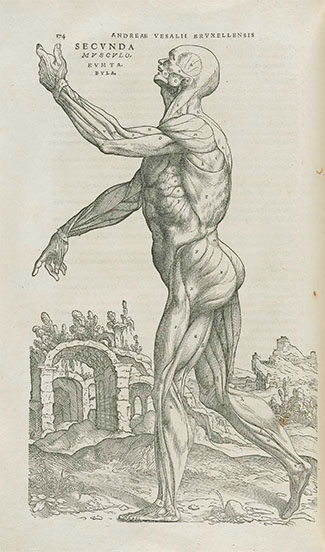

Old school anatomy lectures with Vesalius himself, located to the right-hand side of the female donor.

In 1543, Andreas Vesalius published the book De humani corporis fabrica, becoming one of the most well-known medical artists in history. He became the first individual to describe mechanical ventilation and was responsible for why the bicuspid valve is known as the mitral valve [5]. He tutored many students, encouraging them to check their findings amongst colleagues, and he studied medicine in parallel with his dissections. All of his findings were in contrast to the common belief of anatomy during the time, which was based on Galen and Hippocrates’ ancient analyses. His works and research were part of a continuation of one of the earliest public health projects to determine the sources of the bubonic plague [5].

Painted in 1768. Dermatomyositis described and identified by scientists in 1891.

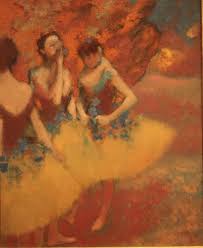

The level of detail in many famous paintings are also so intricate that physicians today can attempt to make diagnoses of the models depicted or the artists themselves. In the painting above, a surgeon at the Imperial College of London identified the man in light purple as having dermatomyositis based on the pattern of the rash on his face with noted Gottron papules on his hands [6]. An ophthalmologist has theorized that Degas’ paintings exhibit deteriorating detail due to progressive loss and worsening of his central vision [6].

Edgar Degas, Dance Class, 1871

Edgar Degas, Three Dancers in Yellow, 1891

As we move into the future of radiographic imaging, holographic imaging and projection, and 3D printing, we cannot forget the legacy of knowledge left behind and initiated by better artists than I.

Alexandra Cooke is a medical student at The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix. She graduated in 2013 from UA with bachelor's degrees in physiology and international studies. This self-proclaimed global health nerd and news junkie can commonly be found downtown exploring local coffee shops and bookstores or out dancing ballroom or swing with friends. In the future, Alexandra hopes to incorporate her passions (somehow) into her medical career and be able to empower patients. She is one of the co-chairs of the Medical Ethics Interest Group.