Think back to the last time you read Romeo and Juliet. It was probably in high school English class, and you were assigned to write an essay on the play’s themes of love, tragedy, or rivalry and also to mix in a discussion about symbolism. Most likely you did a quick search on Sparknotes and found a decent analysis about the statue of the young lovers simultaneously representing the only way they can be together but also remaining forever trapped in the Montague and Capulet feud even after death. While lines like “a rose by any other name would smell as sweet” are often quoted and studied for their linguistic implications, Shakespeare plays also hide a surprising amount of medical references. Take, for instance, Friar Lawrence’s opening monologue from Act II, Scene iii [1]:

O mickle is the powerful grace that lies

In herbs, plants, stones, and their true qualities:

For nought so vile that on the earth doth live

But to the earth some special good doth give,

Nor aught so good but strain’d from that fair use

Revolts from true birth, stumbling on abuse:

Virtue itself turns vice, being misapplied;

And vice sometimes by action dignified.

With the infant rind of this small flower

Poison hath residence and medicine power:

For this, being smelt, with that part cheers each part;

Being tasted, slays all senses with the heart.

Two such opposed kings encamp them still

In man as well as herbs, grace and rude will.

Here Friar Lawrence reflects on the duality of medicinal herbs in their ability to both “cheer” and “slay.” It is possible that the plant in reference is the foxglove, which gives us digitalis or digoxin to treat heart failure. In Shakespeare’s time, the flower was already used as a folk remedy for certain ailments, but it was also common knowledge that the foxglove, if ingested, was poisonous and caused death [2, 3]. Such practices of herbal extractions were becoming popular during the Elizabethan era through the work of Paracelsus, the Father of Pharmacology [4]. He, along with the early Greek anatomist and physician Galen are alluded to in Shakespeare’s All’s Well That Ends Well, the play that features physician and daughter of historical doctor Gerard de Narbon as the heroine protagonist Helena who cures the French king of his fistula.

Although Shakespeare’s surprising medical knowledge is scattered throughout his works—by one count, 712 medical references, including mentions of pia mater and the third ventricles—his sharpest insights about the practice of medicine are through his characters [4]. In describing Helena’s father, the Countess lauds that his “skill was almost as great as his honesty; had it stretched so far, would have made nature immortal, and death should have play for lack of work” (I, i, 15-18). In the same conversation, she says of Helena: “her dispositions she inherits, which makes fair gifts fairer; for where an unclean mind carries virtuous qualities, there commendations go with pity—they are virtues and traitors too: in her they are the better for their simpleness; she derives her honesty, and achieves her goodness” (I, i, 34-39). This latter statement parallels Friar Lawrence’s aforementioned observation that medicine’s powerful dichotomy is in herbs and man, that only its use with integrity (“grace”) can produce the desired healing result.

Indeed, the most prominent healer and restorer of balance throughout Shakespeare’s plays is the Fool. True to its archetype, the Fool in all plays brings laughter in the face of challenges, life after death. In many cases, the Fool is the sole voice of reason as the only character with the perspicacity to see through disguises, quagmires, and crossed fates, and thereby able to deliver the union of couples and broken families, facilitating comedy out of tragedy. Even if they have been wronged and experienced loss, as in King Lear’s companion, Kent, the Fool still serves the other characters in seeking resolution to their conflicts while always maintaining humility. (Without a Fool, the play almost always ends in tragedy; note that the ‘fool’ in Romeo and Juliet was Mercutio who [spoiler alert] unfortunately died too early in act III, scene i, and, in his final moments, curses both houses.)

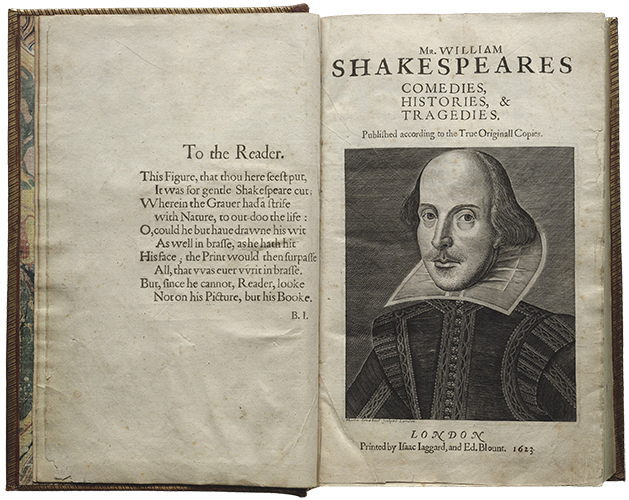

Thus, Shakespeare’s legacy is more than just torturing high school students with analyzing melodramatic love stories and cheesy lines like, “It is the East, and Juliet the sun!” His plays provide a snapshot in the history of medicine and even encourage practicing medicine with a focus on character, morals, and humility. His healers are those who use the skills of observation to understand complicated characters who are always more than their archetypes. So, if you have the time, pick up Romeo and Juliet, Twelfth Night, or Macbeth again, or select a play you previously have not read (I would recommend avoiding Hamlet for now, though, unless you really want to delve into an analysis of madness) and see what knowledge you can pick up to apply at the bedside. The play format lends itself to being useful for understanding character because there is only dialogue that facilitates the plot, so readers must learn to interpret the character behind the spoken words (akin to learning about a patient through their narrative history). And if you find yourself intrigued, inspired, and indefatigable of Shakespeare, be sure to visit the Arizona State Museum at the UA main campus for the exhibition of First Folio! The Book That Gave Us Shakespeare and the companion exhibit Shakespeare’s Contemporaries and Elizabethan Culture, available until March 15.

[1] Arizona Libraries. Shakespeare’s Contemporaries and Elizabethan Culture, a companion exhibition to the installation of the First Folio! The Book That Gave Us Shakespeare at the Arizona State Museum. 2016.

[2] Watkins CJ. Pharmacology Clear and Simple, 2nd Ed. Philadelphia, PA: F.A. David Company. 2013. https://books.google.com/books?id=2Yr2AAAAQBAJ&lpg=PA6&ots=PLG527kqoj&dq=was%20foxglove%20used%20in%20the%201500s&pg=PA6#v=onepage&q=was%20foxglove%20used%20in%20the%201500s&f=false

[3] Gibson AC. The Lifesaving Foxglove. http://botgard.ucla.edu/html/botanytextbooks/economicbotany/Digitalis/index.html

[4] Frank M. Davis. Shakespeare’s Medical Knowledge: How did he acquire it? The Oxfordian. Volume III. 2000. http://shakespeareoxfordfellowship.org/wp-content/uploads/Oxfordian2000_Davis_Medical_Knowledge.pdf

Aishan Shi is a fourth-year medical student and recent MBA grad from UA COM-Phoenix. She graduated in 2013 from The University of Arizona with bachelor’s degrees in biochemistry, molecular and cellular biology, and English. Her interests include medical humanities, structural biology, Shakespeare, stuff in the realm of postmodernism, and cartoons. She aims to bring all these interests together in medicine. To contact Aishan, please email her at ashi1[at]email.arizona.edu.