I wrote this piece to reconcile my feelings and thoughts about choosing a specialty as I have moved through the first two years of medical school. I’m sharing with the hope that these thoughts may impact others (even if it’s just one person) to think about their specialty of choice in a different way. I also write this with an understanding that these thoughts will likely change as I progress through clerkship experiences.

My grandfather, a cardiothoracic surgeon, used to have a plastic model heart that sat on his desk in his home office. When I was a little girl, I used to sit on his lap at his desk and flip open the little doors on the model that opened into the four chambers. I had a fascination with the “white strings” inside and the blue and red lines that ran along the outside of the heart. I wanted to know what everything did and why it was there. My grandpa used to explain these things as simply as possible to me—his curious first-born, six-year-old granddaughter.

On the shelf in his home office, my grandpa also had a framed picture of himself in the operating room. The colors in the picture were washed out and the equipment in the operating room looked old compared to what I, an idealistic 6-year-old, imagined it would be. But to me, my grandpa looked like a superhero. He was right in the middle of the ten other people in the room, his arms and elbows deep inside his trusting patient. He used to tell stories of his cases, and he would express his deep love for his job and patients.

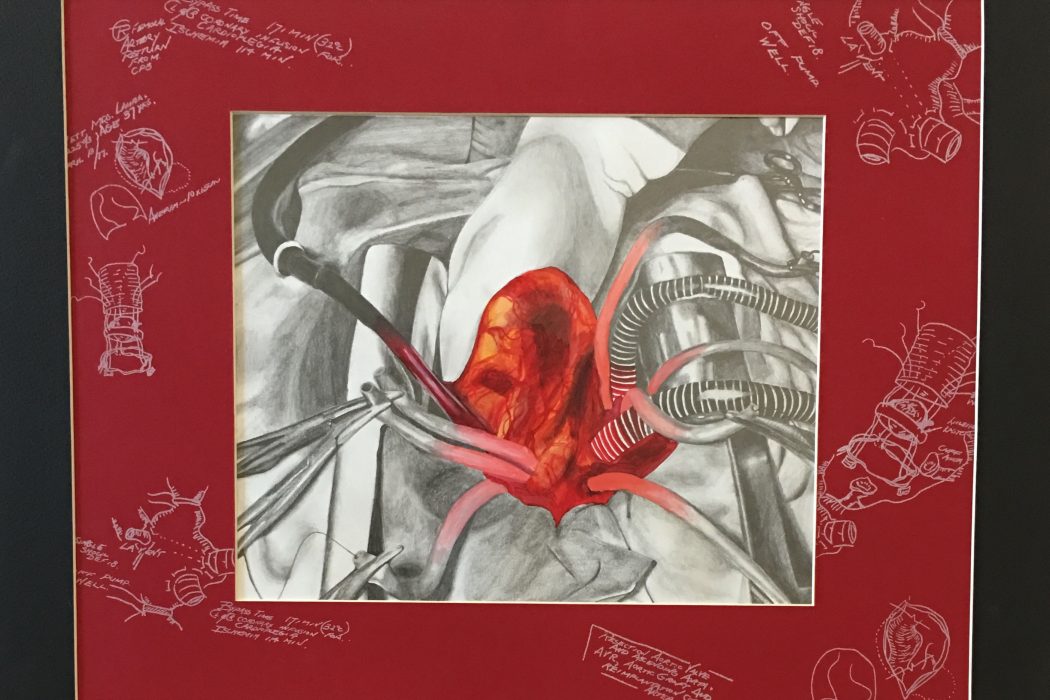

“In Our Hands” by Madalyn Nelson. Completed in 2010.

When I started high school, I took an anatomy and physiology class. I learned that those “white strings” in the model heart were called chordae tendineae. I learned that the blue lines of the model were veins draining the deoxygenated blood from the heart and that the red lines were coronary arteries bringing fresh, oxygenated blood to the always working heart muscle. The more I learned, the less the heart seemed to be an enchanted object. It made sense to me. It has an important job, just like the surgeons who fix them.

Throughout high school, I learned that my grandpa was even more impressive and caring than my 6-year-old self could have imagined. I discovered during one of his office cleaning projects that he had an anatomical drawing for every patient he ever operated on. The drawings generally had two hearts—one with the anatomy of the diseased heart and one that showed the intervention he was going to perform (grafts & valve replacements). My grandpa had at least 40 three-inch binders to hold the thousands upon thousands of drawings for every single one of his patients.

As my grandpa’s love for medicine took hold of me so did my realization that I had his artistic ability. During my senior year of AP Art, I decided that my year-long themed project would be called “Diseases.” Each piece of art embodied a different medical condition, illness, or disease. I had a piece on cancer and a piece on myopia and hyperopia, to name a couple. My favorite one, even to this day, is the one I did of my grandpa holding a heart. I even copied his notes and small drawings of the surgery onto the border of the piece.

I discovered my love for medicine through my grandfather. Medicine was enchanting to me at a young age, and the patient care, management, and research enchant me still. My early exposure to cardiothoracic surgery led me to start medical school hoping to eventually match into surgery. But as I reflect on my discovery of medicine through my grandfather and my first two years of medical school, I realize how drastically my thoughts about what specialty I should choose and what it means to be a doctor have evolved.

I used to think that the only way I could be satisfied as a physician was to be a surgeon and hold someone’s heart in my hand. I thought that I needed to be elbows deep in someone’s chest to make a difference in their life. But now I realize that medicine is so much more than that. It simply and truly is about holding the patient’s heart in your hand. Not literally (as undoubtedly awesome as it is) but figuratively.

Holding a patient’s heart in your hands means listening to their fears and making them feel comfortable to share uncomfortable things with you. It means making the time to sit with them through bad news and celebrate the good news. It means cheering them on when they take their medication every day for a month and encouraging and helping them to find a solution when they do not.

Holding their heart means being there. And no specialty has a monopoly on that.

As we move forward into our medical careers, let us not focus on the specialty that makes the most money or sounds the most impressive. Let us follow our passion (be that surgery or primary care), listen to our values, and think about the countless patients who will rely on us. Because in the end, we’re all just humans with living, beating hearts, looking for someone who cares enough to hold ours.

Madalyn Nelson is part of the 2020 class at The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix. She is an Arizona native and graduated from Xavier University where she earned her bachelor’s degree in biology. Madalyn has a passion for traveling and global health. To contact Madalyn, please email her at madalyndnelson[at]email.arizona.edu.