I remember the three months between finishing college and starting medical school, feeling the combination of nervousness and excitement as I tried to imagine what medical school would be like. Three years later, I look back at that twenty-one-year-old, bright, shining, and ready to take on the world. I was a mixture of naïveté and good intentions. The first two years of medical school were challenging academically, but it was my third year, seeing patients, doing rounds, and hearing stories, that changed me the most.

Throughout my third year, I learned how hard it was to help someone in the way I imagined before starting medical school. I determined, quite quickly, that I am a fixer. During rounds or in clinic, I felt like I wasn’t actually improving the lives of patients, and I easily became frustrated and disappointed. When I said, “ I want to help people,” in my personal statement, I think I really meant, “I want to save people.” I began to realize that there are very few instances in medicine where you actually save people, and fewer still where you see the outcome.

I’ve seen things I wish I could take back and heard stories that have haunted me. As I progressed through third year, I started to appreciate how things no longer upset me. I’d never seen someone die before I came to medical school. When my patient on trauma surgery coded, I felt nothing, and I was surprised at how normal it seemed. Before medical school, I’d never had a personal conversation with a homeless person or someone with schizophrenia or someone high on meth. Things I knew about at a distance, I saw up close. Medicine is unique in that it allows you to insert yourself into someone’s story, to learn extremely private things in the first few minutes of meeting someone. Sometimes I found I didn’t want to know their pain and brokenness.

Shortly after beginning third year, I lost the sense of meaning and purpose of why I went into medicine. Combined with my belief that I wasn’t actually helping anyone, I felt drained, weary, and incompetent. I did not know it at that time, but my transition into third year was complicated by depression. It seeped into my veins, poisoned my brain, and made me feel like a stranger in my own mind. In terms of medical school, I thought I had made a mistake, and I even considered taking a leave of absence. A lifelong perfectionist and overachiever, I was humbled and even ashamed of the fact that I wasn’t doing well, that I wasn’t loving medical school. With support from my friends, classmates, counseling, and medication, I started to improve. I learned several important lessons from this experience. One is that sometimes patients aren’t the only ones who need help. Another is that it’s ok to not be ok. Asking for help is not a sign of failure. Practicing good medicine is not only about being kind to our patients but also to our colleagues and ourselves.

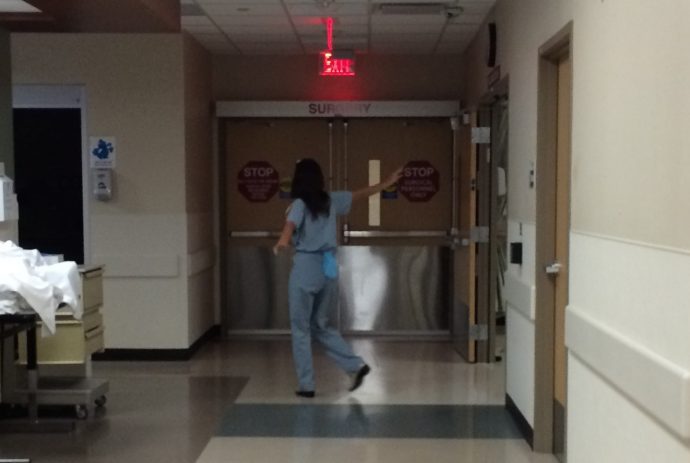

I felt passionate for the first time in third year when I was on my surgery rotation, like I’d found my place. I enjoyed running around the hospital, always something to do. I loved seeing the tangible results of the day’s work, of removing something that should not be there and fixing something that was broken. I had never worked harder, and I had never been happier in medical school. I did a 28-hour call on trauma surgery at Maricopa on my birthday, and it was one of the most memorable I’ve ever had (complete with frozen yogurt from the cafeteria at one o’clock in the morning). In the operating room, I finally felt like I was helping the patient, and I was truly making a difference. My classmates and friends could see it, too. They were the ones who convinced me to look into orthopedics even though I never rotated through the specialty. As a ourth year, I recently completed my

first orthopedics rotation, and I loved it. If you had told me as an MS1 that I would be applying to orthopedic surgery for residency, I would not have believed you. But through all of the ups and downs of my first three years, through the confusion and frustration and late nights and board exams and phone calls in tears to best friends, I am grateful I have ended up here.

By the end of third year, I realized my definition of helping people was flawed, which accounted for a great deal of the discouragement I felt early on. I learned that while getting results was validating, I could still make a difference without ever seeing the conclusion. Having a discussion, showing compassion, and being there for someone may not have a measurable and quantifiable outcome, but it does make a difference. Dr. Paul Brand, a missionary surgeon, says it best when talking about treating patients with leprosy: “I began to see my chief contribution as one I had not studied in medical school: to join with my patients as a partner in the task of restoring dignity to a broken spirit. That is the true meaning of rehabilitation . . . Our mechanical rearrangement of muscles, tendons, and bones was but one step in rebuilding a damaged life. The patients themselves were the ones who traveled the difficult path.”

By the end of third year, I realized my definition of helping people was flawed, which accounted for a great deal of the discouragement I felt early on. I learned that while getting results was validating, I could still make a difference without ever seeing the conclusion. Having a discussion, showing compassion, and being there for someone may not have a measurable and quantifiable outcome, but it does make a difference. Dr. Paul Brand, a missionary surgeon, says it best when talking about treating patients with leprosy: “I began to see my chief contribution as one I had not studied in medical school: to join with my patients as a partner in the task of restoring dignity to a broken spirit. That is the true meaning of rehabilitation . . . Our mechanical rearrangement of muscles, tendons, and bones was but one step in rebuilding a damaged life. The patients themselves were the ones who traveled the difficult path.”

Throughout medical school, there have been days I questioned if it was all worth it. I know I will continue to do so. As I become a resident and then an attending, I hope I will still think it was worth it. I will continue to try to make a difference, not in my own expectations but by meeting people where they are and in showing kindness, to patients and myself, even when I cannot offer much else. I will strive to attain the words of our beautiful but idealistic class oath that we wrote in our first two weeks of medical school: “ . . . cure whenever possible and comfort always.”

Julia Bedard is a fourth-year medical student at UA COM-Phoenix. After spending her childhood in Canada, she moved to Prescott, AZ, in 2001. She attended The University of Arizona, where she was a cheerleader and a total nerd. She graduated in 2013 with a dual degree in physiology and psychology. Her interests include running, hiking, cooking, baking, and coffee. Please feel free to contact her at jbedard[at]email.arizona.edu.