Week after week, my peers and I witness the countless inequities that people experiencing homelessness at each of our Street Medicine Phoenix service events face every day. Through street outreach, our goal is to meet the unmet health needs of people who live on the streets and may not otherwise be able to access care. Of the over 650,000 people experiencing homelessness in the United States, about 40% experience unsheltered homelessness, making access to care and resources even more difficult.1 Every person I meet has a unique story to tell, and it has been eye-opening for me to learn about the health disparities that our unhoused neighbors experience. Paralleling my experiences in Street Medicine with my hospital and clinic-based work, I am struck by the stark differences in reception of healthcare that I see among unhoused patients, especially as it relates to preventative medicine.

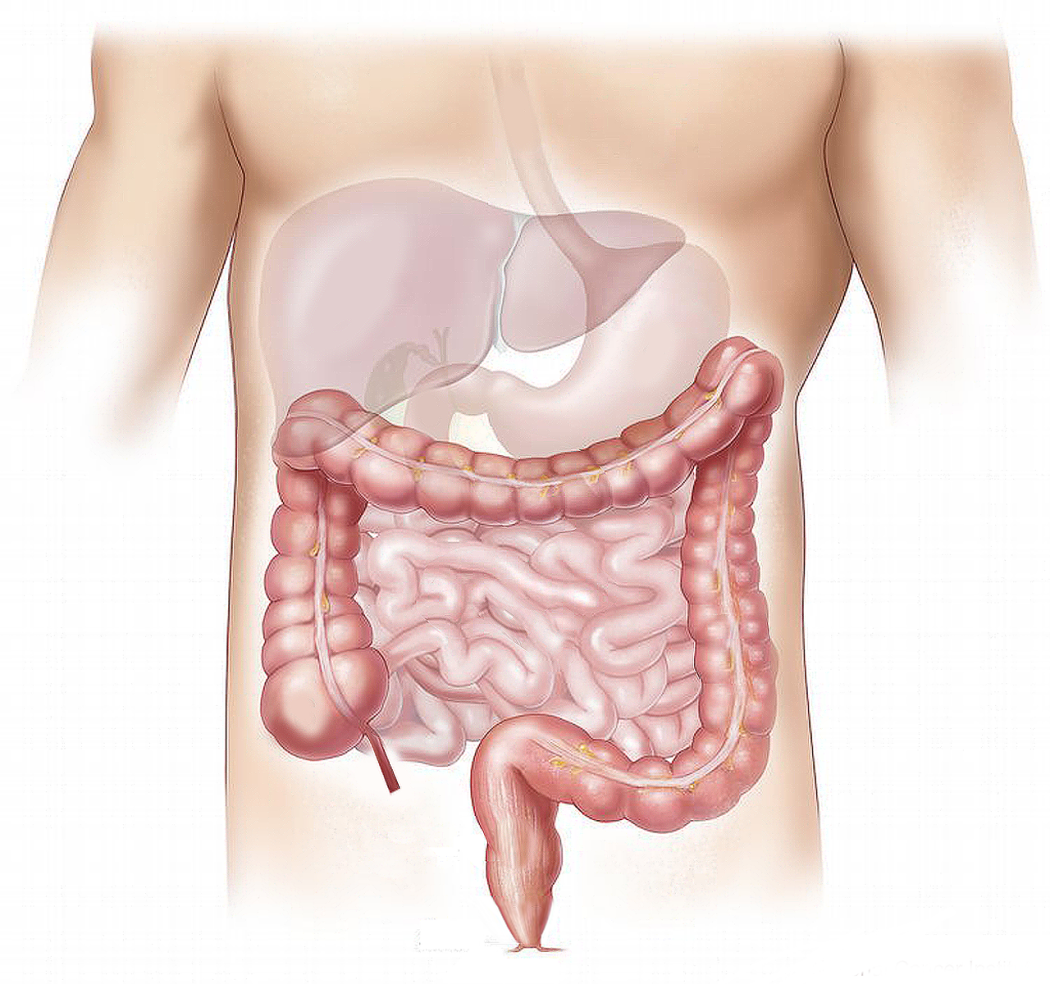

One topic in preventative medicine that I find interesting is colorectal cancer (CRC) screening. CRC is the third most common cancer diagnosis and the second most common cause of death from cancer in the general population.2 CRC screening is relevant starting at age 45 for most people. Many modalities of CRC screening exist, with colonoscopy considered the gold standard and other options including sigmoidoscopy, fecal immunochemical tests (FIT), and fecal occult blood tests (FOBT). However, none of these modalities are feasible unless you have basic access to health care, a private bathroom, clean running water, and more. As I consider the national screening guidelines, it seems clear to me that there is more nuance when applied to the homeless population, given already established disparities in access to care.

Hoping to become more familiar with CRC in people experiencing homelessness, I turned to the literature. Limited studies exist on the topic but the literature available highlights concerning disparities. Recent studies have found that people experiencing homelessness have increased mortality from CRC and are diagnosed with more severe stages of CRC than those in the general population.3-4 Regarding screening, studies in the US have identified significantly lower rates of CRC screening in the unhoused population compared to the general population, with differences of up to 25% depending on the study, although these may still underestimate the true disparity.5-10

Why is that? Is it because CRC screening may not be a priority for patients among other more pressing health and social needs? Are barriers to care or lack of private spaces to complete bowel prep or stool tests the issue? Would it be futile to screen for CRC since obtaining the needed treatment may be infeasible?

Limited studies exist on perceptions of cancer screening among the homeless population. Two studies that explored this found that unhoused individuals actually had positive attitudes towards cancer screening in general, were concerned about cancer, and considered cancer screening to be a priority, despite established barriers to screening.5,11 This suggests that unhoused individuals may in fact value screening, and that attitudes towards screening seem less likely to be the driving factor of disparities.

The disparities in CRC screening rates may therefore be more attributed to barriers to screening. The existing literature suggests that multiple barriers to CRC screening exist, a fact that many of us who have worked with this population would not find surprising. These include lack of stable housing, access to consistent care, private bathrooms, transportation, accompaniment to appointments, communication methods, and mental health conditions.8-9,12-16 Interestingly, lack of provider counseling about CRC screening was also found to be a barrier, likely due to providers’ perceptions and implicit bias of patients’ need, willingness, or ability to complete screening.8-9,13-14,17

Several interventions to address barriers to CRC screening are proposed in the literature, including increasing access to stable housing and private bathrooms, employing patient navigators and case workers, encouraging FIT or FOBT for primary screening rather than colonoscopy, improving patient education, mitigating provider misconceptions, addressing risk factors in the population, and implementing policy and societal changes.5,8,11,13,18,19 Stable housing represents the most overarching barrier as it leads to a sequelae of related social determinants of health, and efforts to address housing insecurity first may be most beneficial. Interventions to improve screening and outcomes require significant buy-in from multiple stakeholders. For providers, assessing the potential benefits of screening based on individuals’ circumstances and engaging in shared decision making are key. Ultimately, our healthcare system should strive to meet people where they are at and needs significant improvement to ensure more equitable care.

Link to the full literature review: https://docs.google.com/document/d/1NUvjeFm1PQw2ajHZLaSs3SQUMfIbACLfU4ZPxKEBuBM/edit?usp=sharing

Note: This was an independent project completed for educational purposes and does not aim to make any universal claims. The contents of the literature review are not to the quality standards of a systematic review that may be found in a peer-reviewed journal.

References

- The U.S. Department of Housing and Urban Development. (2023). The 2023 Annual Homelessness Assessment Report (AHAR to Congress) Part 1: Point-In-Time Estimates of Homelessness, December 2023.

- Lotfollahzadeh, S., Recio-Boiles, A., & Cagir, B. (2023). Colon Cancer. In StatPearls. StatPearls Publishing. http://www.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/books/NBK470380/

- Baggett, T. P., Chang, Y., Porneala, B. C., Bharel, M., Singer, D. E., & Rigotti, N. A. (2015). Disparities in Cancer Incidence, Stage, and Mortality at Boston Health Care for the Homeless Program. American Journal of Preventive Medicine, 49(5), 694–702. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.amepre.2015.03.038

- Decker, H. C., Graham, L. A., Titan, A., Kanzaria, H. K., Hawn, M. T., Kushel, M., & Wick, E. (2023). Housing Status, Cancer Care, and Associated Outcomes Among US Veterans. JAMA Network Open, 6(12), e2349143. https://doi.org/10.1001/jamanetworkopen.2023.49143

- Chau, S., Chin, M., Chang, J., Luecha, A., Cheng, E., Schlesinger, J., Rao, V., Huang, D., Maxwell, A. E., Usatine, R., Bastani, R., & Gelberg, L. (2002). Cancer risk behaviors and screening rates among homeless adults in Los Angeles County. Cancer Epidemiology, Biomarkers & Prevention: A Publication of the American Association for Cancer Research, Cosponsored by the American Society of Preventive Oncology, 11(5), 431–438.

- Lebrun-Harris, L. A., Baggett, T. P., Jenkins, D. M., Sripipatana, A., Sharma, R., Hayashi, A. S., Daly, C. A., & Ngo-Metzger, Q. (2013). Health status and health care experiences among homeless patients in federally supported health centers: Findings from the 2009 patient survey. Health Services Research, 48(3), 992–1017. https://doi.org/10.1111/1475-6773.12009

- Williams, L. B., McCall, A., Looney, S. W., Joshua, T., & Tingen, M. S. (2018). Demographic, psychosocial, and behavioral associations with cancer screening among a homeless population. Public Health Nursing (Boston, Mass.), 35(4), 281–290. https://doi.org/10.1111/phn.12391

- Asgary, R., Garland, V., Jakubowski, A., & Sckell, B. (2014). Colorectal cancer screening among the homeless population of New York City shelter-based clinics. American Journal of Public Health, 104(7), 1307–1313. https://doi.org/10.2105/AJPH.2013.301792

- Marron, T. U., Weiner, A., & Rabiner, M. (2014). Barriers to colonoscopy among New York City homeless. Gastrointestinal Endoscopy, 80(4), 745–746. https://doi.org/10.1016/j.gie.2014.05.309

- Rogers, C. R., Robinson, C. D., Arroyo, C., Obidike, O. J., Sewali, B., & Okuyemi, K. S. (2017). Colorectal Cancer Screening Uptake’s Association With Psychosocial and Sociodemographic Factors Among Homeless Blacks and Whites. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 44(6), 928–936. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198117734284

- Asgary, R., Sckell, B., Alcabes, A., Naderi, R., & Ogedegbe, G. (2015). Perspectives of cancer and cancer screening among homeless adults of New York City shelter-based clinics: A qualitative approach. Cancer Causes & Control: CCC, 26(10), 1429–1438. https://doi.org/10.1007/s10552-015-0634-0

- Centra, T., & Fogg, C. (2023). Addressing barriers to colorectal cancer screening in a federally qualified health center. Journal of the American Association of Nurse Practitioners, 35(7), 415–424. https://doi.org/10.1097/JXX.0000000000000828

- Asgary, R. (2018). Cancer screening in the homeless population. The Lancet. Oncology, 19(7), e344–e350. https://doi.org/10.1016/S1470-2045(18)30200-6

- Drescher, N. R., & Oladeru, O. T. (2023). Cancer Screening, Treatment, and Outcomes in Persons Experiencing Homelessness: Shifting the Lens to an Understudied Population. JCO Oncology Practice, 19(3), 103–105. https://doi.org/10.1200/OP.22.00720

- Rogers, C. R., Robinson, C. D., Arroyo, C., Obidike, O. J., Sewali, B., & Okuyemi, K. S. (2017). Colorectal Cancer Screening Uptake’s Association With Psychosocial and Sociodemographic Factors Among Homeless Blacks and Whites. Health Education & Behavior: The Official Publication of the Society for Public Health Education, 44(6), 928–936. https://doi.org/10.1177/1090198117734284

- Folsom, D. P., McCahill, M., Bartels, S. J., Lindamer, L. A., Ganiats, T. G., & Jeste, D. V. (2002). Medical comorbidity and receipt of medical care by older homeless people with schizophrenia or depression. Psychiatric Services (Washington, D.C.), 53(11), 1456–1460. https://doi.org/10.1176/appi.ps.53.11.1456

- Williams, E. D. (2023). Healthcare Leadership Perceptions of Screening for Social Risk Factors, Toward Colorectal Cancer Screening Uptake [D.H.A., Franklin University]. https://www.proquest.com/docview/2814212603/abstract/E46DACE99BB348FCPQ/1

- Schwartz, H. E. M., Abel, M. K., Lin, J. A., Decker, H. C., Kushel, M. B., & Wick, E. C. (2022). Barriers to Colorectal Cancer Screening and Surveillance in Homeless Patients: A Case Report and Policy Recommendations. Annals of Surgery Open: Perspectives of Surgical History, Education, and Clinical Approaches, 3(3), e183. https://doi.org/10.1097/AS9.0000000000000183

- Hardin, V., Tangka, F. K. L., Wood, T., Boisseau, B., Hoover, S., DeGroff, A., Boehm, J., & Subramanian, S. (2020). The Effectiveness and Cost to Improve Colorectal Cancer Screening in a Federally Qualified Homeless Clinic in Eastern Kentucky. Health Promotion Practice, 21(6), 905–909. https://doi.org/10.1177/1524839920954165

Likith (Lucky) Surendra

Likith (Lucky) Surendra is a medical student at the University of Arizona College of Medicine - Phoenix, Class of 2024. He is from Phoenix and graduated from Arizona State University with Bachelors degrees in Biological Sciences and Business. He is an MS4 Co-Lead of Street Medicine Phoenix and has been volunteering with the organization since 2019. He is planning to pursue Internal Medicine for residency. In his free time, he enjoys spending time with family and friends, driving and working on cars, and playing video games.