“The life of a single human being is worth a million time more than all the property of the richest man on earth.”

Quote by Ernesto “Ché” Guevara above the entrance to the Calixto Garcia Hospital.

On August 19, 1960, the revolutionary physician, Ernesto “Che” Guevara, formally addressed the Cuban Militia. His speech has since been published and distributed as an essay entitled On Revolutionary Medicine [1]. Through telling stories of his own personal journey throughout the Americas, Guevara outlines the basic principles of his new brand of medicine. These values in which he sees in the future “revolutionary doctors” include a preventative focus, a desire to integrate into their patients’ communities, the want to provide care regardless of economic class or ability to pay, a value of the whole over the individual, and the want to expand the revolution.

Today, Raul Castro touts his state-run health system as a crowning achievement of Cuban communism. The island’s impressive health statistics demonstrate this dedication to the health of the nation’s public. Despite its low GDP, Cuba’s average life expectancy and child mortality public health statistics rival those in the United States [2]. How is this possible? What the tiny island nation lacks in pharmaceuticals, materials and technologies, it makes up in human resources. Cuba has one of the highest doctor-to-patient ratios in the world with one physician per every 170 people [3]. They also graduate six thousand doctors per year from their 26 medical schools. Cuba’s doctor-producing capacity has outgrown their domestic needs.

A Cuban community primary care doctor’s office. In Havana, these are just about on every other block. The physician lives in the room upstairs and has a clinic on the first floor. They live in the neighborhoods of their patients and make house visits regularly. According to this physician, they are “always on call because everyone in their neighborhood knows where they live.”

Cuba is exporting physicians as well as the Cuban idea of medicine. This variety of medicine is becoming increasingly well-known in the poorest communities of Latin America, the Caribbean, and parts of Africa where Cuban and Cuban-trained doctors are practicing. Additionally, defections and non-authorized foreign medical practice from the government are frequent, further spreading Cuban medicine into developed nations [3].

Cuba’s first foreign medical aid mission was 1963 as part of Cuba’s foreign policy of supporting anti-colonial struggles [4]. Cuba sent a small medical brigade to Algeria, which suffered from the mass withdrawal of French medical personnel during their war for independence. Additionally, there was a small amount of early non-revolutionary aid, usually in the form of emergency disaster relief as opposed to a sustained medical effort. Cuba sent medical teams to earthquake reliefs frequently, such as to Chile in 1969, Nicaragua in 1972, and Iran in 1990 [4]. “When I went to Iran, they did not want us to leave,” said one cardiologist who spent months in the rural mountains north of Tehran. “Truthfully, there were more non-traumatic injuries that we treated. Not because of the earthquake, but because these people had never seen a doctor in their life.”

In Guevara’s ideal system, physicians were the foot soldiers of the revolution. As the notion of health and illness expanded outside a simple biochemical realm, the role physicians played altered too, particularly with prevention. Along with ensuring that the basic needs of the Cuban people were met, prevention began to take a function of ensuring that the revolution prospered [5]. As Guevara said, “We shall see that diseases need not always be treated as they are in big-city hospitals. We shall see that the doctor has to be a farmer also and plant new foods and sow, by example, the desire to consume new foods, to diversify the Cuban nutritional structure, which is so limited, so poor, in one of the richest countries in the world, agriculturally and potentially.” Guevara’s ideal of having doctor-farmers is not that far off from Cuban reality today. Cuba has no shortage of trained healthcare professionals. Because of this, physicians work in areas of public health prevention that are not seen as the responsibility of allopathic medical doctors in many other western nations. This includes clean water initiatives, sanitation and even art therapy. One doctor told me about his experience in Haiti where he “helped dig wells and taught cooking techniques without using charcoal. The smoke kept causing them respiratory and eye problems.”

The Cuban government is attempting to address one of largest ethical dilemmas today: the issue of global inequity in healthcare. Starting with medical outreach to Honduras, Guatemala, and Haiti after Hurricane Mitch in 1998, Cuban medical missions started changing their focus to semi-permanent forces fostering international cooperation. Huish writes about the impact in Honduras showing that “In the areas they served, infant mortality rates were reduced from 30.8 to 10.1 per 1,000 live births and maternal mortality rates from 48.1 to 22.4 per 1,000 live births between 1998 and 2003” [6].

Geographic, economic, and educational barriers create an imbalance in access to quality care. Underserved areas are found even in countries with well-established healthcare systems but unequal medical access is even more drastic in developing countries. Developing countries tend to not only have fewer medical resources, but also a substantial deficit of trained physicians [7]. Cuba has made it a national priority to not only make sure that rural Cubans have access to healthcare, but also to ensure that nations abroad are equipped with medical personnel. Cuba often exchanges these healthcare services for self-interested reasons, either in the form of subsidized commodities or direct compensation. However, there are other times when there are no clear economic or political motives behind their healthcare aid efforts.

Today, Cuba relieves physician shortages internationally by sending their Cuban doctors abroad on medical tours. In 2013, Cuba had over 38,000 government-employed physicians providing care in over 76 foreign countries [8]. This is a larger workforce than the Red Cross, Medicines sans Frontieres, and UNICEF combined. Since then, the number of physicians, nurses, and other medical technicians serving abroad has grown to over 50,000. These individuals serve in a variety of areas providing not only emergency response, but also long-term community-based care. Cuba also believes that providing these community-based doctors can overcome current structures of inequity and exploitation on a global scale by providing care in marginalized communities on a cost-effective basis [9].

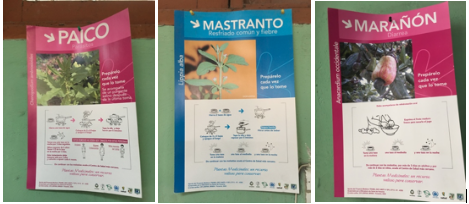

Due to financial restrictions, Cuba has had to develop some creative solutions to pharmaceutical drug shortages. An increased reliance on natural and herbal remedies is one solution. These are some examples of posters that are seen in a primary care office.

Cuba is able to entice doctors to travel abroad for several reasons. The most persuasive reason is a substantial pay increase. Dr. Ortiz-Labrada, a defected doctor in Tampa, told me, “Don’t believe any doctors that say they are going to these places out of the kindness of their hearts… That is part of it, but these foreign deployments are highly sought after because you make way more money.” When I asked how much more money doctors make while abroad, they said that it depends, but generally double or triple the salary of a doctor in Cuba. Additionally, there is an element of adventure, especially in going to Africa, that medical students and young doctors find very appealing. “I want to go to Angola, like my dad did,” said one medical student. “They need our help very badly.”

The second way that Cuba is addressing the worldwide doctor shortage is through training foreign citizens who pledge to serve the citizens in their own countries. In addition to over a dozen medical schools and multiple residency programs that train Cubans and foreigners alike, Cuba has a special school called the Latin American Medical School (ELAM) for training foreign doctors. Since its first class of 2005, ELAM has graduated over 23,000 physicians from low-income communities in Africa, Asia and the Americas [7]. This is possible due to the full scholarships offered by Cuba, made on the condition that the new physicians make a commitment to work in underserved areas upon graduation. Cuba’s contribution is an important long-term solution to the human resources crisis facing many developing nations.

The Latin American School Of Medicine is the biggest medical school in the world. This school accepts students from all over the world (including the United States) for training free of charge. One condition is that you return to your home country to serve in an underserved community.

To conclude, medical internationalism has been practiced by Cuba since the triumph of its revolution. Consistent with Che’s ideas of “exporting revolution,” the earliest medical missions were accompanied by military efforts to foster “anti-imperialist” sentiments in certain countries. Starting in the early 1990s, Cuba’s international export of medicine began to grow tremendously. It was also fueled by different motives including financial compensation, the acclimation of “soft power,” and fostering international cooperation [8].

- Guevara, C. (2005). On revolutionary medicine. Monthly Review, 56(8), 40.

- WHO releases latest health statistics report.(news)(brief article). (2014). Bulletin of the World Health Organization, 92(6), 391. doi:10.2471/BLT.14.010614

- Huish, R. (2009). How Cuba’s Latin American School of Medicine challenges the ethics of physician migration. Social Science & Medicine, 69(3), 301-304. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2009.03.004

- Huish, R. (2013). Where no doctor has gone before: Cuba’s place in the global health landscape Wilfrid Laurier Univ. Press.

- Brouwer, S. (2009). The cuban revolutionary doctor: The ultimate weapon of solidarity. Monthly Review, 60(8), 28.

- Huish, R., & Kirk, J. M. (2007). Cuban medical internationalism and the development of the Latin American School of Medicine. Latin American Perspectives, 34(6), 77-92.

- Brouwer, S. B. (2011). Revolutionary doctors: How Venezuela and Cuba are changing the world’s conception of health care. NYU Press.

- Huish, R. (2014). Why does cuba ‘care’ so much? understanding the epistemology of solidarity in global health outreach. Public Health Ethics, 7(3), 261-276. doi:10.1093/phe/phu033

- Farmer, P. (2003). Pathologies of power: Health, human rights, and the new war on the poor. North American Dialogue, 6(1), 1-4.

Samuel Beger is a class of 2021 medical and Master of Public Health student at The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix. He earned his B.S. in Anthropology and his M.A. in Applied Ethics at Arizona State University where he spent weeks in Cuba shadowing and interviewing physicians. Before attending medical school, Sam worked as an E.D. tech and founded a Phoenix-based coffee roasting company.