We learn a lot from what we see. We invent visual modalities that capture our surroundings, converting them into numbers to be shared and studied. Medicine has manipulated physics and made these forces visible—radiation, sound, the oscillation of hydrogen ions in water. These scientific marvels are how we made X-rays, ultrasounds, CTs, and MRIs possible. We appreciate a good picture, and incorporating media and video into healthcare education feels like a natural consequence of these innovations, made ever so convenient in the modern day.

We use them to learn, and often our learning materials come from real patients. De-identified, of course, but what can be said when that isn’t the case? Hiding behind grayscale makes it easy, but what if we are confronted with bleeding color? What if we are faced with their faces?

We are used to looking at portrayals of conditions, and so, we may start to forget. Remember that we learn from the suffering of others, as well as simply the mere existence of others. We are learning of ourselves, of our own humanness by extension.

Children with genetic conditions, their portraits scaled up onto the projector. School photos and family photos, toothy smiles adorned in primary color sweaters. Their photo propped up beside a block of text. The morphologic differences are notable, but do not forget these are snapshots of their childhood. There is the memorization of chromosome abnormalities and syndromes, but there is also the becoming familiar with a face from years ago, looking to whomever stood in front of the camera. These are moments and memories of strangers being seen by first-years.

Capturing neurology on camera, the off-screen doctor comfortably gives context and commands. The patient—who we very well could have been in their place—eyes the camera and waits for their cue. They try the best they can to teach and not forget a detail, reciting it all as accurately as they could. Faceless medical students will be watching, after all. Patients asked to walk, to stand, to overcome dystonias and to demonstrate how they ambulate onto a wheelchair, a sense of selflessness follows as they move. They take in a breath and retell their medical history in the privacy of a cardiologist office we are now privy to. Walking across the room, and back, silence fills the room as we study them. We may not learn their name, but will never forget how they made us feel.

Grainy videos of patients from the 80s, 90s, early 2000s—even some recent and fresh from capture—they teach people they’ll never see, hoping that some portion of them lives in the hippocampus of future doctors. The videos remain in circulation because they are so effective, and we are hardwired to notice: notice the neurologic deficit, for a pathology, for a gait abnormality, but there is more than just that, and to be open to more than that. When we learn what differentiates dementia from delirium, one may notice more than the subtle signs and symptoms; woven in is the very real attempts of patients sharing their life experiences that persist outside the frame and stay with us well after class.

Pictures of rashes, of scars, of injuries, be it superficial or deep—tragic injuries and evidence of their worst days (or rather, their new normal)—these are parts of a person forever frozen in time. They may be our initial introduction, and even shape how we view and expect a condition to resemble, even at the expense of nuance, such as how a dermatological condition may present on varying complexions. These photographs and videos may affect how we perceive the patient’s quality of life and their life itself. How many of these modalities do we see in a day? How many people do we learn from in a day?

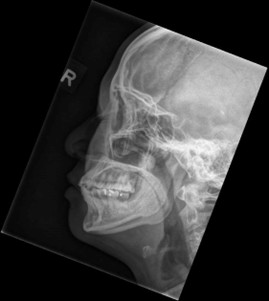

They’re our introduction to conditions, a face to the long Latin or Greek name (or both), they are the basis of pattern recognition. Their life experiences are captured into a short window of time, but it may be relived many times. The microscopic portrait on a slide, the autopsy finding, the X-ray film, all nameless pieces of people—there is a degree of awe that comes with not only the widespread access of learning within reach, but also the drive to teach others. They stay with us, this part of them, having guided us in our medical education.

To end, the image cover for this article (and featured again here) is a x-ray of a 40 yo woman who was physically assaulted, with only bruising and no fractures to indicate on radiography. Would you have known?

References

- https://pmc.ncbi.nlm.nih.gov/articles/PMC8202324/

- https://digitalcommons.library.tmc.edu/cgi/viewcontent.cgi?article=1716&context=utgsbs_dissertationshttps://radiopaedia.org/cases/normal-facial-bones-series.

Fatemah Alzuhairi

Fatemah Alzuhairi is a UACOMP med student from the class of 2028. She graduated from ASU in 2022 with a degree in biomedical sciences and a minor in history. In her spare time, she enjoys planning creative projects, reading, and drinking copious amounts of Earl Grey tea.