I’m writing this article from 30,000 feet above Albuquerque, en route to the East Coast, where I will spend the next several days re-entering the world as a healthy and well-adjusted human. I have spent the last month sitting alone in a small corner of my apartment, studying for 10 hours each day in preparation for one of the universally dreaded milestones required to become a physician: the USMLE Step 1 exam.

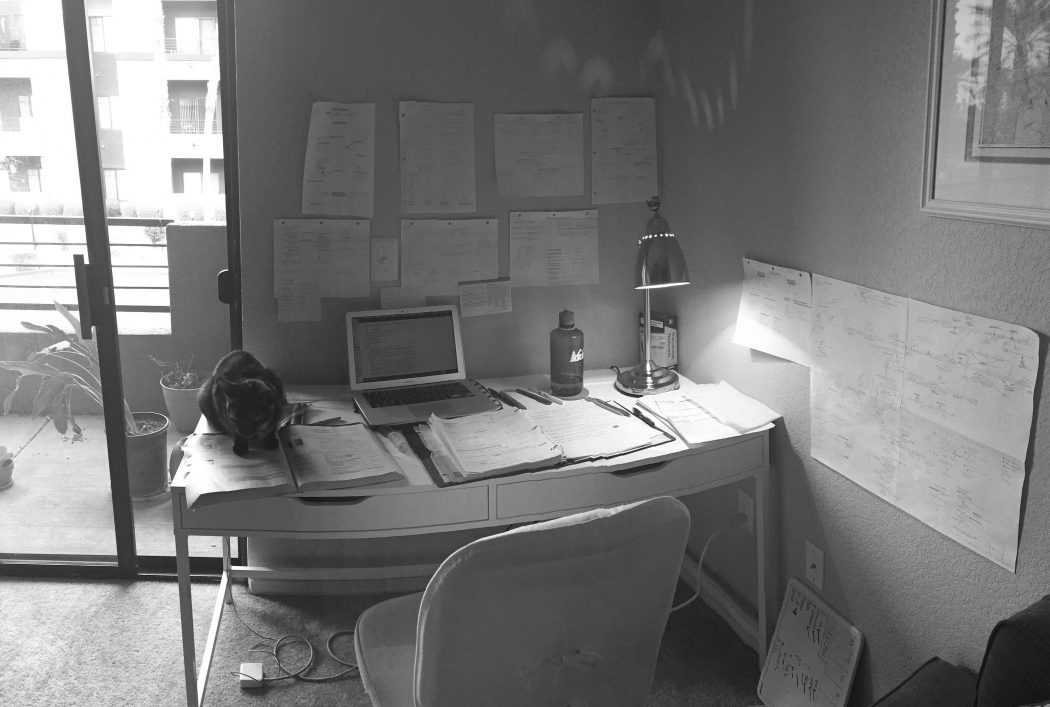

My workspace one week prior to taking Step 1.

Hello, from the other side.

There are infinite stories of medical students becoming overwhelmed with depression and anxiety while studying for this formidable exam. Medical schools dedicate mandatory sessions to discussing warning signs, showing videos of “real students” spiraling into pits of despair, having wished they asked for help sooner. I am 30 years old and have wrestled with generalized anxiety disorder for most of my life, far before I knew it had a name or DSM criteria. My symptoms have been well controlled for years. Perhaps, this is why I proudly assumed I would be immune to the agony of the solitary and exhausting existence that is “dedicated study time”—a period of 4-8 weeks when medical students are given time off to study for their first board exam. I believed I had learned to channel my anxiety into productivity.

That was until I found myself in a doctor’s office attached to an electrocardiograph, absolutely convinced that I had developed a heart arrhythmia. Minutes later, the nurse unceremoniously handed me a pamphlet on anxiety and asked if I had tried any breathing exercises (answer: I have). Anxiety had insidiously crept back from the hinterlands of my amygdala, first taking hold of my rational thought processes and eventually waking me multiple times each night with a pounding heartbeat. I had subconsciously reverted to old habits: obsessively creating daily study schedules, sometimes down to the minute, and punishing myself if I strayed from this arbitrary assignment. I withdrew from customary phone calls with friends and family. I was overcome with panic attacks for the first time in two years.

I knew I was losing my grip on reality, but I was helpless in staunching my rapidly deteriorating brain chemistry. Over the years, I’ve started referring to the nadir of my anxiety as “panic blackout”—a state when my mind becomes blank and the pressure of an exam smothers me. This is not an ideal situation to find oneself in weeks before facing off against an 8-hour standardized test.

Anxiety and depression are quite prevalent in medical students (as in the general population, for that matter); however, they are uncommonly discussed on an interpersonal level. Discourse about mental health issues is especially delicate in medicine for fear that peers will pass judgment and future employers will pass over applications. Unlike other disorders that present with physical pain, disability, or the need for constant monitoring, anxiety can be concealed and the sufferer often endures in secrecy. My struggle with anxiety is often private—it is challenging to meaningfully convey the intangible workings of a reverberating mind. Those without anxiety encouragingly offer “don’t worry” as a solution to the mountain of irrational thoughts and somatic symptoms that I experience daily.

I am certainly not the only student who has been tormented by my preparation for Step 1. I constantly wonder what changes in medical culture could prevent students with and without pre-existing mental illness from succumbing to the pressures of such a high-stakes exam.

It is clear that an increasing number of medical students paired with a static quantity of residency positions is a significant factor that continues to drive the mounting strain. According to the National Resident Matching Program, the organization responsible for the algorithm that matches graduating students with residency programs, 94% of residencies list USMLE Step 1 scores as a key factor in interview selection, and 68% require students to meet a cutoff score. Average scores have risen as well. The mean USMLE Step 1 score for U.S. & Canadian examinees climbed from 217 in 2005 to 229 in 2015. As obstacles accumulate, it seems only natural that medical students experience heightened levels of apprehension.

Medical schools recognize these growing challenges, and students are instructed to develop a robust self-care routine, theoretically learning to prevent and predict what can sometimes be an unexpected degeneration of mental health. Developing strategies for coping with stress is a valid suggestion. Exercise, proper sleep hygiene, social support systems, and potentially therapy should be part of medical students’ self-care toolkits. But are these solutions a panacea?

The descent towards “dedicated study time” is treated like disaster preparation. The panic level increases as the time approaches and students frantically begin discussing what and how much to study. They compare resources, question banks, and practice exam scores. Friends and family outside of medical school are warned of their loved one’s impending hibernation. For me, the most wearisome and anxiety-inducing aspect of dedicated time was the reclusion. Being alone with my incessantly running ticker tape of thoughts was overwhelming: “Am I answering enough questions correctly? Have I dedicated enough hours? What score do I need in order to match into my desired field? What’s that lump in my neck? How big should lymph nodes feel? (Things tend to spiral downward from here).” Cutting ties with friends and family during this time seemed antithetical, and I began spending at least an hour each night sitting on the couch with a friend, discussing the monotony of our days. This one routine gave me something to look forward to and may have kept me from completely succumbing to my neuroses.

The psychological stress of standardized testing has become ingrained in the culture of medicine. But need it feel this way? Have we become so inured to the status quo of standardized testing that we no longer question the potentially unreasonable sacrifices taken to reach our goals?

It will take effort not only from students but also from faculty, administrators and practicing physicians to tackle “big testing.” While medical students alone may not be able to immediately achieve systemic changes, individuals can take the initiative to stem escalating anxiety in our own communities. Instead of sharing practice exam scores and number of hours studied, share meals and yoga classes. Resist self-sabotage by avoiding incessantly accessing forums about how to achieve the highest score or fretting over the methods other students may use to study. Trust that you have survived two years of medical school by coming to understand the most effective study methods for you personally. Do not accept Step 1 as the rate-limiting step in the journey towards becoming a physician. And if you find yourself fighting back the high tide of anxiety, remember: there are others who know this struggle. You too will regain your grip on reality.

Michelle Blumenschine is a medical student in the Class of 2018. She holds degrees in film & TV production and journalism & mass communication from New York University and completed her pre-med post-bac certificate at Columbia University. Before moving to Phoenix from New York City, Michelle worked as a documentary film producer. She enjoys making to-do lists, drinking craft beer, and collecting National Geographic magazines. She is pursuing a career in obstetrics and gynecology.