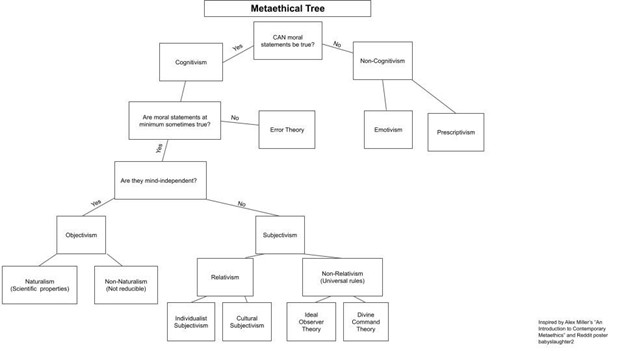

Welcome back to my Medical Ethics Series for the third installment! This is the final part in the metaethics series before we move on to Normative ethics (Utilitarianism, Deontology, etc.). As a reminder, in the first edition we discussed in general terms what metaethics is, touched on the concept of moral authority, and dove deeper into moral motivation. In the second edition, we discussed the initial branches of the metaethical tree (see bottom), including Cognitivism and Error Theory. We then went down the rabbit hole and looked at branches of Cognitivism, focusing on Subjectivism, which we broke down Subjectivism into Relativism and Non-Relativism, and we explored these areas own sub-sub-branches, namely Individualist Subjectivism, Cultural Subjectivism, Ideal Observer Theory, and Divine Command Theory. It was a packed article, and this time we are doing a lot less I promise!

Since last time we went down the Subjectivism half of Cognitivism, this time we will check out the other side, Objectivism -let’s get to it!

Where does morality come from? (Objectivism)

Objectivism

This is the idea that moral claims are mind-independent, or do not need people to be true, moral rules simply exist1. Objectivism’s appeal comes from offering a solution to the intuition we have about morality. If things are objective, then it makes sense why we pursue morality, why societies seem to morally improve throughout history, and it tells us how to achieve our goals (empirically find morals). Moreover, it just sounds right that if something is wrong then it is wrong. However, how morality “exists” is up for debate and results in two branches of Objectivism: Naturalism and Non-Naturalism. Briefly, Naturalism thinks that morals are properties like light and sound waves, things we can discover empirically. This gives us good reason to be moral, as like with physics, they are laws of nature, and it would be irrational to fight it. The Non-Naturalist also thinks morals are objective, but holds that morality is of a supernatural-esque type, supervening on our physical lives, a force above us.

Naturalism

Naturalism holds that moral facts are inherent to the world much like atoms. Naturalists believe that we can uncover moral truths through science, just as we uncover physical laws like gravity. Once we know these truths, rationality compels us to follow them. In conclusion, we should be moral because fighting it is irrational2. Awesome, right? The strength to this theory is apparent; if morality is something we can discover, then Subjectivism’s flaws are solved, depressing theories like Nihilism are defunct, and we can one day discover what is truly right. In a world increasingly occupied with science, and as people who study science ourselves, this is of great appeal.

As beautiful as it sounds, naturalism has some problems to address. A famous counter-argument is Hume’s Is/Ought gap, where he attacked the Naturalist’s idea of deriving moral facts from natural facts: Just because we know what something IS (descriptive/natural), doesn’t mean we know what we OUGHT to do (judgement/moral).

Example:

1. Our patient is a person.

2. People don’t like getting bad medical treatment.

3. I ought not give my patient poor medical treatment.

This conclusion doesn’t quite flow, despite having accurate facts about the first two premises, nothing in that argument says WHY I ought not give them bad treatment. You have to fill in the statement “you ought not do what people don’t like” to make the logic flow.

Modified Example:

1. Our patient is a person.

2. People don’t like getting bad medical treatment.

3. You ought not to do what people don’t like

4. I ought not give my patient poor medical treatment.

But then we have to add in this judgement/moral statement (“you ought not do what people don’t like”) and the question arises why we should accept this added judgment/moral as binding. There seems to be no “natural law” as to why this judgement statement exists other than that we appraise it to be true. Although this counter-argument has been dampened by rebuttals over time, it demonstrates some ways in which other attacks may approach tearing down Naturalism. If you are curious about more robust but complex arguments against it, check out G.E. Moore’s Open Question Argument (see Non-Naturalism below), as well as ideas attacking Naturalism’s failure to explain moral motivation (see Medical Ethics Series #1 – Laying the Groundwork).

Non-Naturalism

Non-Naturalism is the idea that morality is a very real thing but “non-reducible” to properties. This is popularly associated with G.E. Moore who we just saw attacking Naturalism. Moore holds that intuitively we know morals exist and this is why we naturally make moral claims such as “helping patients is good”, and from this he insists morals are Objective. However, he believes in Non-Naturalism over Naturalism as morality appears “non-reducible” to lesser properties. Scientifically, we can always reduce something to its components, such as molecules being made of atoms, which are made of protons and neutrons, and so on. If morality is a property, then we should be able to reduce it to its components much like those molecules, but Moore says we can’t. He exemplifies this by showing that we cannot define the word “good”, much like how we can’t define the color yellow. If you had never seen yellow before, could someone describe it to you? They could provide you with all the physical properties of something colored yellow, but could they describe the experience of yellow to you?*

Moore says no, you cannot describe yellow to someone who hasn’t seen it, and therefore cannot describe “good”, an attempt to do so he calls the Naturalistic Fallacy. From this he tells us “good” is irreducible to a physical property, thereover rejecting Naturalism3.

In his Open Question Argument, he somewhat undermines other opposing theories as well. In brief, his argument states that a statement is closed if it provides a definition. An example would be “a square has four sides”. An open question is something that does not give us the answer, such as “His arm was broken, but was it still functional?” To Moore, the definition of “good” seems to leave open questions rather than closed statements3. This is a bit complicated so let’s take an example.

Example:

Here’s a Cultural Subjectivism claim: “Canadian culture permits physician-assisted suicide, therefore it is good.” (X=Y)

Example:

Moore’s response: “Your culture permits it, but is it actually good?” This is an open question, as to him X does NOT answer Y.

To Moore, this ability to always create an open question shows there is something more to defining goodness and therefore we should reject claims that try to do so.

Red flags pop up immediately at his rejection of Subjectivism, as it seems to assume the conclusion (Beg the Question). If, unlike him, you think the term “good” is merely descriptive, then the Open Question Argument seems silly! Of course I told you what was good, it’s what my culture decided, aren’t you listening, Moore?

Further, how does this Non-Natural property “supervene” on us, that is, how does it interact? If it is not a natural property, not some scientific fact, where is it? How does it compel us to act good? How exactly does it tell us assisted suicide is wrong? There are a host of other counter-arguments, but the very attempt to remove the weaknesses of Naturalism seem to create even more for the Non-Naturalist.

*If you are interested in pursuing this fascinating line of ideas, this argument borrows a concept from Philosophy of Mind and the Mary’s Room thought experiment.

Let’s Sum It All Up

That was a lot, so I will recap:

Objectivism is the concept that morality is inherent to the universe, not up to us, and completely objective. The manner of existence for these morals splits between Naturalism and Non-Naturalism, with the former believing morality is reducible to properties much like science, and the latter insisting it is non-reducible and “supervenes” upon us.

This concludes our exploration of the main metaethical theories, although I left off some larger ones such as Nihilism & Skepticism for the sake of time. If they are interesting to you, however, please let me know and I will see if I can make an article on them too!Now that we have finished with Metaethics, the exploration of what is ethics, and why to be ethical, we can move on to Normative ethics, or the question of what specific rules and principles are right. Through Dr. Beyda, people are loosely familiar with some famous Normative theories such as Utilitarianism, Deontology, and Virtue Ethics. I intend to deepen this understanding for readers and myself alike, so that we may take away more from his valuable lectures. That’s all for now! I hope you’ll be here next time when we discuss the simplistic beauty and dangerous pitfalls of Utilitarianism!

References

- https://iep.utm.edu/moralrea/

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/naturalism-moral/

- https://plato.stanford.edu/entries/moral-non-naturalism/

Travis Seideman

Travis Seideman is a member of the Class of 2026 at UACOM-P. He attended Northern Arizona University where he studied Exercise Science and Psychology. He is planning on practicing rural Family Medicine and pursuing a fellowship in Sports Medicine.