I remember the moment when I first decided that I wanted to be a physician. I was five, and I was walking out of a store with my family in rural upstate New York. Obsessed with dinosaurs at the time, I proclaimed that I was going to be a “cardiojurassic surgeon.” In addition to having the unusual target population of dinosaurs, I had this vision of what being a doctor meant: a patient would come to me with a problem, and I, as the person filled with knowledge and answers, would solve their problem with compassion. I would, literally and figuratively, bandage them up and send them on their way with a smile.

The reality in medicine, however, is often far from that simplistic vision that I held as a child. Reality looks a little more like this:

My first patient of the day, a young boy with severe asthma, lives in poverty in a neighborhood next to a highway filled with smog and pollutants that contribute to regular asthma exacerbations.

My second patient has a poor diet and is sedentary, with multiple chronic diseases that are caused and aggravated by her lifestyle. Yet, lifestyle changes are near impossible when she has to work three jobs to make ends meet and also lives in one of our nation’s many “food deserts” [1].

What I have learned in my short time in medicine is that my patients will often come to me with a myriad of issues, a minority of which I can actually solve with a maneuver, test, or prescription pad. In lieu of a short-term bandage for their problem, many of my patients need solutions to poverty, food insecurity, equitable access to education, safe neighborhoods, environmental justice, and criminal justice reform. All of these are cures that lie not within the doctor’s office but in the realm of public policy.

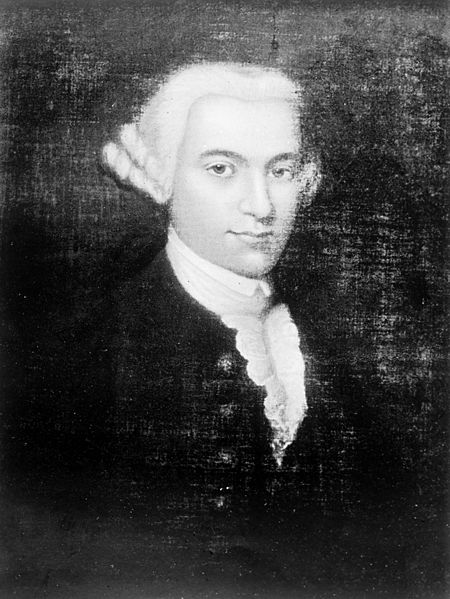

Thomas Percival (1740-1804), English Physician.

The involvement of physicians in shaping public policy is not a new concept. As far back as the 1770s, Thomas Percival, an English physician, lead the charge to reform policy regarding occupational health. Percival had a large influence on the development of the Health and Morals of Apprentices Act of 1802, a law that placed limits on child labor, introduced sanitation regulations, and required factories to allow health inspections [2]. The notion that physicians have a duty to be involved in public policy has continued into the 21st century. In 2001, the American Medical Association (AMA) described the duty of physicians to act on public policy in an oath called the Declaration of Professional Responsibility: Medicine’s Social Contract with Humanity. Amongst the usual duties of a physician to treat the ill, educate future physicians, and protect patient confidentiality lie two additional declarations: that physicians should commit themselves to “educate the public and polity about present and future threats to the health of humanity” and “advocate for social, economic, educational, and political changes that ameliorate suffering and contribute to human well-being” [3].

While the history of the involvement of physicians in civic service is long, not all agree that physician involvement in politics is appropriate. Opponents of the inclusion of advocacy as a professional commitment for physicians argue that civic involvement is outside of the professional realm and that there is danger in politicizing medicine. Opponents also voice concern that fostering advocacy in medicine may undermine the efforts of physicians to be objective and, particularly in academic medicine, can shift the focus from collecting knowledge to creating change [4].

Additionally, despite calls for physicians to be actively involved in shaping the health of their communities, physicians engage in community and political activities less often than those of similar incomes, with less than 25% of physicians reporting that they engage in political activity beyond showing up to vote [4-5]. It seems, then, that a dilemma remains for many physicians: What is our responsibility as healthcare providers to move beyond the exam room and into the murky arena of policy? Should we step aside, erring on the side of neutrality, and leave politics to the politicians? Or should we speak up about the issues that impact the health of our patients and our communities?

- Food Deserts. United States Department of Agriculture Web Site. http://apps.ams.usda.gov/fooddeserts/fooddeserts.aspx Accessed August 7, 2015.

- Howard JK. Dr Thomas Percival and the Beginnings of Industrial Legislation. Occ Med. 1975; 25(2): 58-65. doi: 10.1093/occmed/25.2.58

- Declaration of Professional Responsibility. American Medical Association Web Site. http://www.ama-assn.org/ama/pub/physician-resources/medical-ethics/declaration-professional-responsibility.page Published December 4, 2001. Accessed August 7, 2015.

- Huddle, TS. Perspective: Medical professionalism and medical education should not involve commitments to political advocacy. Acad Med. 2011; (86)3: 378-83. doi: 10.1097/ACM.0b013e3182086efe

- Grande D, Armstrong K. Community volunteerism of US physicians. J Gen Intern Med. 2008; 23(12): 1987-1991. doi: 10.1007/s11606-008-0811-x

Photo: Thomas Percival, from WikiCommons: https://commons.wikimedia.org/wiki/File:Portrait_of_Thomas_Percival_Wellcome_M0000721.jpg

Alex Geiger is a medical student at The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix. He completed his Master of Public Health (MPH) at Arizona State University and his BS in biological sciences at the University of Connecticut. He is passionate about public health, policy, and health economics with a particular interest in how these issues impact underserved communities. Feel free to contact Alex at amgannon[at]email.arizona.edu