The first time I saw the donor I was to dissect for the next several months, truthfully and somewhat embarrassingly, I thought wow she has amazing breasts. My tablemates and I all jumped to pathological conclusions (breast cancer, naturally) when we found her implants. At the end of anatomy, we learned her cause of death, which had nothing to do with her breasts. This left me wondering at the end of our time together why was it so impossible for us to imagine someone full of life, desires, and the natural human instinct to want a good-looking body?

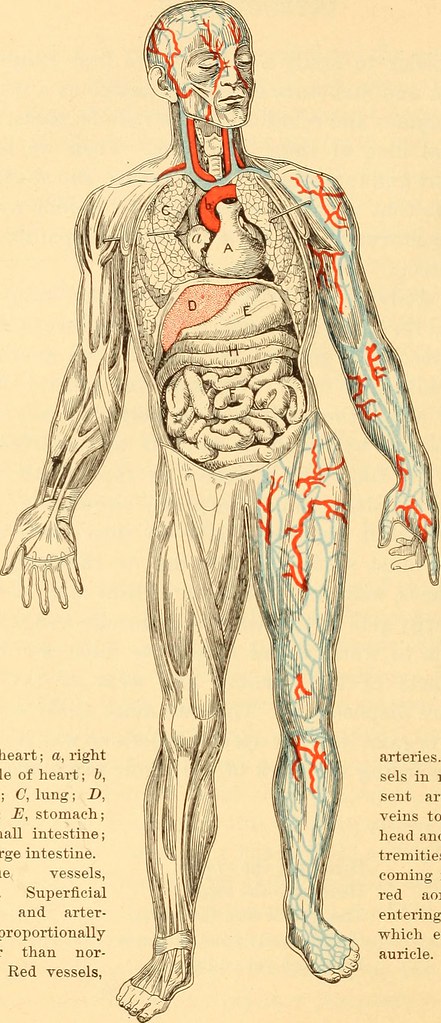

It was hard to keep the idea of her as a living person coupled with the visceral body on the table in front of me. It is a lot easier to see the arm as a detached limb, the stomach as a part of an organ system, and even the head as just another abstracted segment. While this is protective in many ways – how could you make it through otherwise – it also is important to note. Often, people turn to this process in anatomy as a pivotal moment in which medical students become less empathetic physicians. Though it may seem strange, this is an important and arguably necessary step in becoming a physician.

The instinct to separate the body into distinct parts is an element of our training. There are ophthalmologists, neurologists, hand specialists… It must be noted that we are monetarily rewarded for becoming more and more myopic in our care. Anatomy is one of the first moments in which we are asked to break down, separate, dissect the body (literally, in this case) while rebuilding an idea of a whole. But – how do future doctors keep in mind the whole person when focused on the disparate parts, especially in the case of highly specialized training?

To return to the whole is a challenge. To begin to see the anatomy of a human not just as its disparate limbs and organ systems, but as interconnected interactions and complexities – some beyond our scope of knowledge – is a challenge. To see the human in front of you not just as a patient and their singular illness, but as one who is full of life, desires, and complexities is a challenge. To learn to accept the nuance, that sometimes, I will be unable to hold all these things together at once is a challenge. Returning to the whole is a challenge, one that I faced in anatomy and will continue to face daily as a physician.

Anna Leah Eisner is a member of The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix, Class of 2026. She was born and raised in LA and graduated from Boston University with a degree in English and Russian Literature. She then taught abroad in Thailand as an elementary school teacher and received a Fulbright in Kyrgyzstan, where she lived in between a library and a holy mountain. She moved back to LA to complete med school prereqs and scribe for an ER. She developed a love of surfing and is now attempting to translate that to Phoenix's sidewalks with a skateboard and a lot of padding.