Many pregnant women at their first check-up will receive a pamphlet with an overview of their pregnancy, genetic testing, things to avoid, prenatal vitamin advice, and – on the back cover in glossy marketing – an ad for private umbilical cord blood banking.

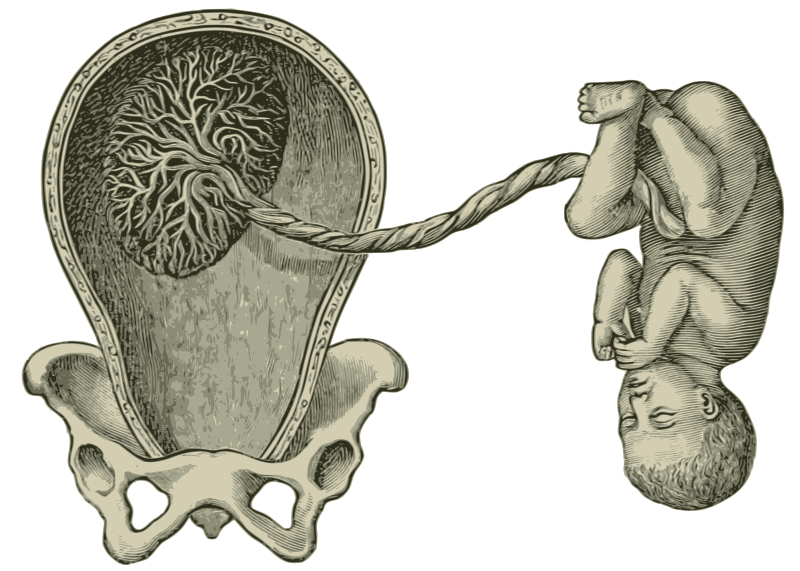

Cord blood is a source of hematopoietic stem cells that can be used to treat a range of diseases including blood cancers, leukemias, and thalassemias. It is usually discarded after a person gives birth, and the potential for collecting these stem cells is also tossed away. Cord blood banking was developed to collect these cells and store them for future use in transplantation.

There are two types of cord blood banking: public and private. Public banking relies on donations from people who have consented to having their cord blood collected; it serves as a fund which the public can access for transplantation. In private banking, couples choose to pay a storage fee for their cord blood to be kept in a bank should other people in their family need the stem cells at some point in their lives.

Needless to say, there are ethical concerns that accompany this process.

Informed consent is probably the initial issue that comes to mind in this process – especially in private cord banking. Private cord banking is costly, averaging about $1,200-2,500 for cord blood collection with storage fees of $50-70 monthly following the initial collection. It also isn’t recommended – both ACOG and the AAP advise against storing a child’s stem cells as “insurance” against future diseases, as the chances that a future family member will need them is small to none. This is due to the low prevalence of such disorders, as well as the need for HLA matching between donor and recipient. Additionally, the tissue won’t be able to be used for the child from whom the cord blood came from, as it contains the same genes that potentially caused the disease.

There are some cases in which private cord blood banking is indicated – for example, when a family member already has one of the diseases for which hematopoietic stem cells are a potential treatment. However, for the most part, private banking is an unnecessary cost.

So when an OB/Gyn office, the first medical touchpoint most women have for their pregnancy, hands over an official pamphlet with an advertisement to bank cord blood privately, there is a lot of information that is missing. The advertising uses fear tactics, preying on some parents’ scariest “what ifs?” by showing a (rare) situation in which a sibling was saved by their parents’ (expensive) foresight of privately banking the cord blood of another child. It’s coming from a trusted source, but it’s misleading, as it represents an infrequent occurrence.

It is anticipated that people will do some research on their own regarding whether or not to bank cord blood. However, there are so many decisions – medical and otherwise – that come with a pregnancy. To a person without experience in medicine, they are often looking to their physicians to answer questions that they have regarding which genetic testing to pursue, how to develop a birthing plan, what foods to avoid, and what activities to pursue. For physicians to provide an advertisement for private cord banking in their initial pamphlet of recommendations is misleading because it can result in people taking on unnecessary costs without any true need.

Additionally, the informed consent process for private collecting of cord blood varies from bank to bank. Often, patients will sign up for cord blood banking and inform their physician of their decision without having a full conversation about the risks (being few) and benefits (also few).

In medicine, there are inherent power dynamics. The trust developed between physician and patient is a deeply important aspect of the healing process. A dependable source advertising, seemingly recommending, a process that is largely discouraged is a violation of that trust. It implies that the patient can also be treated as an economic opportunity, not solely a person for whom to care. Furthermore, variations in informed consent create confusion and lead to a lack of full information being given to patients.

What is to be done with cord blood then? It is admittedly an incredible resource, as its collection has few risks and many potential benefits for those with disorders that require hematopoietic transplantation. Public cord banking is the option that ACOG and the AAP recommend to pregnant people, as it is free to the person who donates, and then can be used in the future for those who are an HLA match.

Additionally, public banking is a much more equitable option. Public banking provides the opportunity to those who do not have the money to privately bank their childrens’ cord blood to still receive life-saving treatments.

With all the big decisions that come with pregnancy, physicians should help alleviate some of the stress by educating people about cord blood, providing them with full information about private and public banking, and helping facilitate the right decision for them – rather than using it as an opportunity to profit.

References

Gerdfaramarzi MS, Bazmi S, Kiani M, Afshar L, Fadavi M, Enjoo SA. Ethical challenges of cord blood banks: a scoping review. J Med Life. 2022;15(6):735-741. doi:10.25122/jml-2021-0162

Booth J, Adams R, MD. Cord Blood Banking: How Much Does It Cost? Forbes. Published February 3, 2022. Available at: https://www.forbes.com/health/family/cord-blood-banking-cost/

American College of Obstetricians and Gynecologists. Cord Blood Banking. Available at: https://www.acog.org/womens-health/faqs/cord-blood-banking#:~:text=Storing%20a%20child%27s%20stem%20cells,for%20directed%20donation%20is%20encouraged

Raine SP. Informed Consent in Umbilical Cord Blood Collection, Storage and Donation: A Bloody Mess. [PDF]. University of Houston Law Center Health Law & Policy Institute; 2007.

Shearer WT, Lubin BH, Cairo MS, Notarangelo LD, et al. Cord Blood Banking for Potential Future Transplantation. Pediatrics. 2017;140(5):e20172695. Published November 1, 2017. doi:10.1542/peds.2017-2695. Available at: https://publications.aap.org/pediatrics/article/140/5/e20172695/37866/Cord-Blood-Banking-for-Potential-Future?autologincheck=redirected

Anna Leah Eisner is a member of The University of Arizona College of Medicine – Phoenix, Class of 2026. She was born and raised in LA and graduated from Boston University with a degree in English and Russian Literature. She then taught abroad in Thailand as an elementary school teacher and received a Fulbright in Kyrgyzstan, where she lived in between a library and a holy mountain. She moved back to LA to complete med school prereqs and scribe for an ER. She developed a love of surfing and is now attempting to translate that to Phoenix's sidewalks with a skateboard and a lot of padding.