I recently attended the Smithsonian’s first virtual museum tour, which addressed the history of contraceptive devices in collaboration with Dittrick Museum of Medical History at Case Western. The curators addressed the main classes of contraceptives and the historical themes of privacy and subtlety that pervaded reproductive health in the early 20th century.

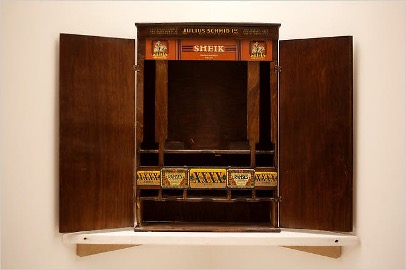

The story starts in the early 1920s with the condom. The most famous condom brand was “Sheik,” which was a famous character who was known as “the world’s greatest lover.” Although the packaging was discrete and classy, condoms were readily available in the drugstore in the 1920s and 1930s. Interestingly, during this time it was illegal to advertise condoms for prevention of pregnancy. Instead, the messaging was “protection against disease.” In fact, condoms were often referred to as “prophylactics” or “pros.” There was a huge fear of venereal diseases during this time, which is apparent in both condom marketing and the government. For example, there were condom vending machines with stickers on them reading “stop VD.” The FDA also began testing condoms for efficacy around this time. However, the use of early condoms did not strike me as particularly sanitary when I learned that they were marketed to be reusable: “guaranteed 5 years.”

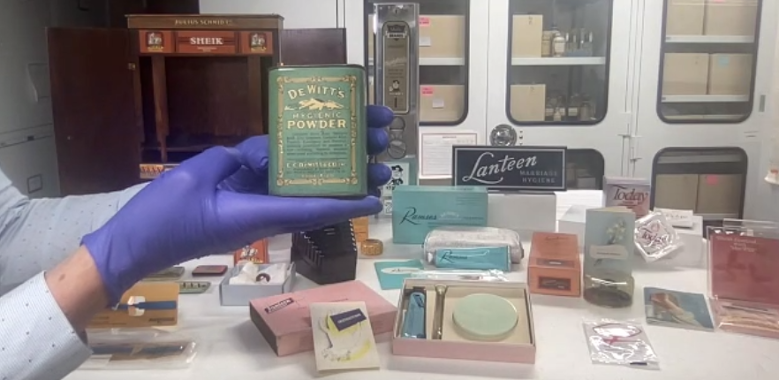

The next items that were discussed involved vaginal douching, which in stark contrast to condoms, were marketed towards women. These chemical agents were the most popular form of contraception prior to the advent of oral contraceptives. The most popular brand was Lysol. Yes, the household cleaning product was aggressively advertised to women for “feminine hygiene.” Of course the instructions were to dilute it, but there were still many issues and complaints regarding the product.

Next, there were diaphragms. These devices were marketed as “marriage hygiene,” which was essentially code for birth control. Unlike the antiseptics used in douching that could be purchased at drug stores, diaphragms were under the purview of physicians. Therefore many women did not have access to these devices because they did not have free access to medical care. If you did have the means to see a doctor, you still had to overcome the challenge of finding one of the few who provided this service. Diaphragms came as part of a kit, and women had to go to the doctor to be custom fit for one. Then they would receive a subtle, pastel-colored box with the diaphragm, an applicator, vaginal jelly and an instruction booklet. The kit in its entirety was marketed as a “tuck away kit” in keeping with the theme of subtlety.

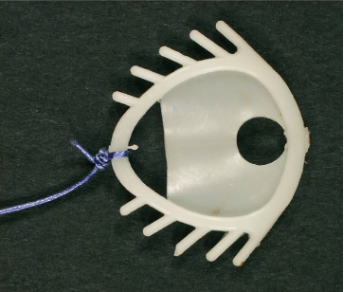

Then in the 1960s there was the invention of oral contraceptives. During this era, “the pill” contained very high levels of hormones and thus side effects such as blood clots were common. Hence, women continued the search for better options. In the 1970s, the Dalkon Shield was introduced and heavily promoted by physicians. This device caused intrauterine infections and inflammation. You might be thinking “of course it did, just look at it.” However, you might be surprised to learn that the infections were due to the braided, porous microfibers of the string and not the spikey-plastic body. Thankfully, this product was eventually recalled in 1984.

This session opened my eyes to the disparities that existed regarding access to reproductive care during the 20th century. For example, some women resorted to applying caustic chemicals intravaginally due to a lack of access to safer options such as diaphragms. These inequalities still exist today in all realms of medicine, including reproductive health. However, there are much safer, superior options in the modern era. It is a reminder of the ability of technology to improve lives and take steps towards health justice. By examining the past, I can see how important it is to continue moving medicine forward through both scientific advances and health advocacy.

Katherine Bracamontes is a student at The University of Arizona College of Medicine-Phoenix class of 2023. She graduated from the University of Southern California in 2015 with a B.S. in Lifespan Health. While living in California she became involved with her local radio station, which fostered an interest in community culture and journalism. Katherine enjoys live music and hiking at a very, very leisurely pace.